Christmas in Albany? Not so much.

The Dutch who settled in Albany celebrated St. Nicholas Day (St Nicholas was also known as Sinterklaas) with feasting and frolics in early December. Sinterklaas was a kindly religious figure in a red robe who brought presents and went down a chimney to fill stockings with presents. But the Dutch reserved Christmas for religious observances and then raised the roof on New Year’s Day, with much merry making and exchanging of gifts. The Protestant Germans who settled here in the 18th century did have a tradition of celebrating St. Nicholas Day and sometimes Christmas as well (the Germans pretty much rocked the whole month of December); such festivities were private –not for public display. BUT the English “Yankees” who came to Albany from New England in the 1700s were not big on Christmas revelry; that was hangover from the Puritans and the Mayflower who actually banned Christmas in the 1600s. At best a pagan ritual; worst case .. celebrating Christmas was blasphemy.

Even after the Revolutionary War, Albany didn’t really have its Christmas groove. But the idea of Christmas was catching on. By 1813 a few ads appear in newspapers for Albany stores selling Christmas as well as New Year’s gifts.

Washington Irving Wins the War on Christmas

Enter Washington Irving, author of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”. In the early 1820’s Irving published five very popular stories about what Christmas was like in Merry Olde England (the English, at least in the Mother Country had transcended their aversion to Christmas). The stories describe holiday customs and traditions: feasting, gifts, mistletoe, music, family games, Yule logs and candles that resound with joy and merriment. Irving’s Christmas Eve is magical. In one of the stories, he makes an actual pitch for Christmas; the traditions are too beautiful to lose and winter is a cruel season – we NEED Christmas. Washington sealed the deal;. his descriptions were enticing and seductive- his descriptions flawless. Who didn’t want to celebrate Christmas? By 1822, the Troy Sentinel publishes “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (a/k/a “The Night before Christmas”) by Clement Moore, an Episcopalian clergyman from Rhinebeck. Christmas is now officially a thing. But we still don’t have a Santa.

Irving had also done a splendid job of describing St, Nicholas Day in his first work, “A History of New York” in 1809; there were other pamphlets and books that told the St. Nicholas story. Over the next decade or so there are more stories about Christmas and St. Nicholas Day until the 2 holidays sort of merge into one. The merging is more of a process, rather than an event. The Dutch edge towards Christmas from St. Nicholas celebrations; the Yankees get the idea it’s ok to have fun on Christmas.. and the Germans, well, it was all good and Gemütlichkeit; Germans never need a reason to party.

The “Yankees” of Albany and New York appropriated the fun Dutch traditions for Christmas. Sinterklaas becomes Santa Claus; he’s described as a decidedly more English Falstaff-like guy.. his clerical robes are exchanged for a red suit and he becomes positively roly-poly. But we still don’t know what he looks like- there are no good pictures to accompany the written descriptions.

Enter Richard H. Pease

Richard Pease was born in Connecticut in 1813. By the mid 1830’s he’d moved to Albany. Pease was a talented lithographer and engraver; also an amazing entrepreneur. In the late 1830s he established Pease’s Great Variety Store at 50 Broadway in Albany. If you wanted it, the Great Variety Store appeared to have it, especially as the “holydays” (holidays) of Christmas and New Year’s came around. Pease was a salesman, and he used his lithography skills to sell his merchandise. In 1842 the first image of Santa Claus as we know him today (almost) is printed in one of Pease’s ads. Pease clearly has read Santa descriptions from the previous decade; the Pease Santa is chunky, with a beard (not yet white) and suit. In his store ad, Santa is ready to climb down a chimney and there is a reindeer on the roof. His bishop’s miter had been traded for a peeked hat.

Richard Pease was born in Connecticut in 1813. By the mid 1830’s he’d moved to Albany. Pease was a talented lithographer and engraver; also an amazing entrepreneur. In the late 1830s he established Pease’s Great Variety Store at 50 Broadway in Albany. If you wanted it, the Great Variety Store appeared to have it, especially as the “holydays” (holidays) of Christmas and New Year’s came around. Pease was a salesman, and he used his lithography skills to sell his merchandise. In 1842 the first image of Santa Claus as we know him today (almost) is printed in one of Pease’s ads. Pease clearly has read Santa descriptions from the previous decade; the Pease Santa is chunky, with a beard (not yet white) and suit. In his store ad, Santa is ready to climb down a chimney and there is a reindeer on the roof. His bishop’s miter had been traded for a peeked hat.

Over the next decades other images of Santa emerge, some very creepy, but Pease’s image gets wide circulation in newspapers across the country for many years. His talent and imagination created the basis for an enduring image of Santa. Thomas Nast, the political cartoonist, creates the next iconic Santa for “Harper’s Weekly” (1880s), drawing on the Pease Santa. The Nast image is finally replaced as the official Santa in the 1930s when Coca-Cola creates a genius ad campaign in the 1930s Depression, designed to get people to drink more soda in the winter. Coke.. it’s not just for summer.

Pease Strikes Again – the first American Christmas Card

The Great Variety Store thrives. By the mid -1840s, Pease moves to a new building at 516 Broadway and opens The Temple of Fancy. Just the name makes you want to shop. It’s basically the ‘Emporium of Everything”. Still a marketing genius, in 1849, he decides to make a special card for Christmas, which is the first Christmas card produced in the Unites States. (The first card ever was created in England in 1843. Alas, Christmas cards don’t really catch on until Boston-based printer Louis Prang started selling color cards in 1875.

What Happened to Albany’s Marketing Genius?

The Temple of Fancy thrives and Pease creates a number of wildly popular children’s books and games. The Temple closes about 1853 when Pease moves on to another successful enterprise. In 1854 Pease purchases the Albany Agricultural Works, and operates it as the Excelsior Agricultural Works with his son Charles, who previously owned a similar business in Tivoli Hollow. It looks like they were quite successful and we are on the trail of a potential Pease patent for a potato planter.

Copyright 2021 Julie O’Connor

CRUSADE AGAINST SHAMELESS VICE screamed the Times Union headline on Monday, November 26, 1900. The Anti-Saloon League mounted a unified attack on drinking, organizing twenty rousing brimfire sermons in as many churches on the same Sunday.

CRUSADE AGAINST SHAMELESS VICE screamed the Times Union headline on Monday, November 26, 1900. The Anti-Saloon League mounted a unified attack on drinking, organizing twenty rousing brimfire sermons in as many churches on the same Sunday.

DISGRACEFUL SCENES

DISGRACEFUL SCENES

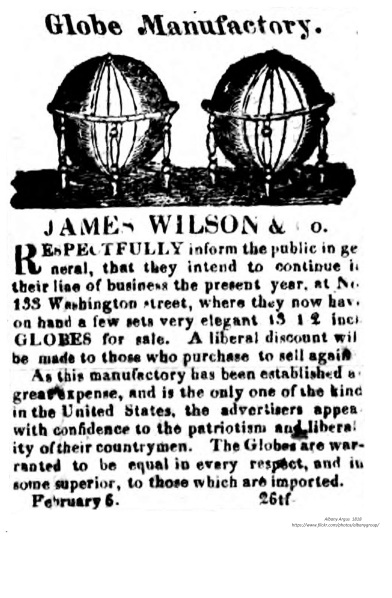

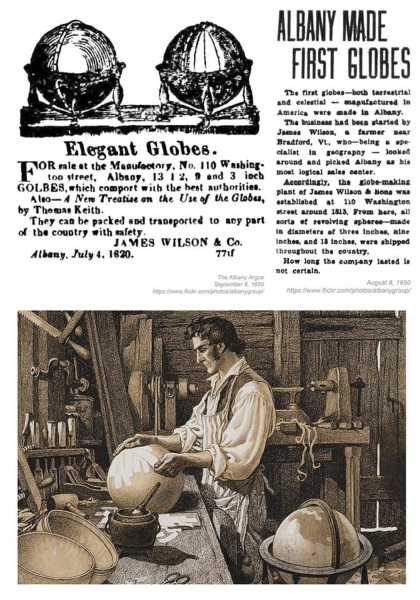

Wilson realized he needed to move his operation to an urban area, but didn’t want to leave the farm, so he sent 2 of his sons to start the business in Albany. The date the Wilson Globe manufactory started in Albany is not clear, although it was about 1815 and most certainly not later than 1817. The location was Washington Ave., but there are various addresses within a 5 year period – 110, 133 and 166 – all in the block between Swan and Dove. The globes were sold directly by the Wilsons and by commission agents in places like New Haven, New York City and Boston, as well as the western parts of New York State.

Wilson realized he needed to move his operation to an urban area, but didn’t want to leave the farm, so he sent 2 of his sons to start the business in Albany. The date the Wilson Globe manufactory started in Albany is not clear, although it was about 1815 and most certainly not later than 1817. The location was Washington Ave., but there are various addresses within a 5 year period – 110, 133 and 166 – all in the block between Swan and Dove. The globes were sold directly by the Wilsons and by commission agents in places like New Haven, New York City and Boston, as well as the western parts of New York State. Initially, the oldest Wilson son Samuel seems to have been in charge of the Albany shop, but a year later, another son, John is running the Albany business in 1818. David, Wilson’s third son, joined his older brothers at Albany, and did the engraving on a forthcoming new edition of three-inch terrestrial and celestial globes. (He left the business in the early 1820s to become a painter of miniatures.)

Initially, the oldest Wilson son Samuel seems to have been in charge of the Albany shop, but a year later, another son, John is running the Albany business in 1818. David, Wilson’s third son, joined his older brothers at Albany, and did the engraving on a forthcoming new edition of three-inch terrestrial and celestial globes. (He left the business in the early 1820s to become a painter of miniatures.)

James Wilson died in 1855 in Bradford Vt, up on the farm he loved. Cyrus Lancaster died 8 years later in Brooklyn.

James Wilson died in 1855 in Bradford Vt, up on the farm he loved. Cyrus Lancaster died 8 years later in Brooklyn.

Blatch tried to re-invent the movement, focusing on women who were self-supporting. Hundreds of thousands of women now worked in factories and the number of business and professional women was growing exponentially. Blatch started working with the newly created Women’s Trade Union League and other unions, following the model of Emmeline Pankhurst in England. But that too proved slow going. Immediate concerns of low wages and poor working conditions distracted from voting rights.

Blatch tried to re-invent the movement, focusing on women who were self-supporting. Hundreds of thousands of women now worked in factories and the number of business and professional women was growing exponentially. Blatch started working with the newly created Women’s Trade Union League and other unions, following the model of Emmeline Pankhurst in England. But that too proved slow going. Immediate concerns of low wages and poor working conditions distracted from voting rights.

Enter a very different society woman who re-energized the movement by her status and pots of money. Alva Vanderbilt Belmont was a force of nature. She was first married to William Vanderbilt (whose claim to fame was the construction of Madison Square Garden). She shocked the work in the 1890s when she divorced Vanderbilt and married Oliver Belmont. Upon his death in 1908, Alva entered the world of women’s suffrage with guns blazing. Alva had notoriously bested “old money” society in NYC when she was married to Vanderbilt and re-invented herself after her divorce. She was determined to set the suffrage world on fire in the same fashion. Alva funded suffrage offices in NYC and Albany. She raised money from other socialites, embraced participation by immigrant and Afro-American women, staged huge demonstrations and rallies with factory workers and supported the massive NYC shirtwaist factory strike of 1909.

Enter a very different society woman who re-energized the movement by her status and pots of money. Alva Vanderbilt Belmont was a force of nature. She was first married to William Vanderbilt (whose claim to fame was the construction of Madison Square Garden). She shocked the work in the 1890s when she divorced Vanderbilt and married Oliver Belmont. Upon his death in 1908, Alva entered the world of women’s suffrage with guns blazing. Alva had notoriously bested “old money” society in NYC when she was married to Vanderbilt and re-invented herself after her divorce. She was determined to set the suffrage world on fire in the same fashion. Alva funded suffrage offices in NYC and Albany. She raised money from other socialites, embraced participation by immigrant and Afro-American women, staged huge demonstrations and rallies with factory workers and supported the massive NYC shirtwaist factory strike of 1909. By 1910 Albany women were back in the game. The next seven years would be series of highs and lows. “Suffrage week” in Albany became a regular thing during the legislative session. News of women’s suffrage moved from the women’s sections of newspapers to front pages and Albany businesses advertised their support for suffrage through newspaper advertisements.

By 1910 Albany women were back in the game. The next seven years would be series of highs and lows. “Suffrage week” in Albany became a regular thing during the legislative session. News of women’s suffrage moved from the women’s sections of newspapers to front pages and Albany businesses advertised their support for suffrage through newspaper advertisements.

Rather than traveling the militant route (rock throwing and resultant forced feedings after arrest) that Emmeline Pankhurst and her followers adopted in England, suffragists in New York State went for the dramatic and newsworthy. With more money they were determined to win the propaganda war. In December 1912 there was a 10 day march in the freezing cold from NYC to Albany to present petitions to the incoming Governor, William Sulzer, a friend of suffrage. Newspaper reporters followed the march and there were newsreel films. Albany supporters met the marchers at South Pearl and Second Ave. as they entered the city and escorted them to the Capitol, accompanied by a band from St. Vincent’s Orphan Asylum. But Sulzer was elected with help of Tammany Hall and turned his back on them in favor of “good government”. He was impeached within 8 months, and the dreams of a statewide vote on women’s suffrage disappeared for 1913.

Rather than traveling the militant route (rock throwing and resultant forced feedings after arrest) that Emmeline Pankhurst and her followers adopted in England, suffragists in New York State went for the dramatic and newsworthy. With more money they were determined to win the propaganda war. In December 1912 there was a 10 day march in the freezing cold from NYC to Albany to present petitions to the incoming Governor, William Sulzer, a friend of suffrage. Newspaper reporters followed the march and there were newsreel films. Albany supporters met the marchers at South Pearl and Second Ave. as they entered the city and escorted them to the Capitol, accompanied by a band from St. Vincent’s Orphan Asylum. But Sulzer was elected with help of Tammany Hall and turned his back on them in favor of “good government”. He was impeached within 8 months, and the dreams of a statewide vote on women’s suffrage disappeared for 1913. In 1914 the suffragists of Albany decided to mass together for a large parade. On Saturday June 6 about 700 men and women from Albany, its environs and across the State, gathered in the late afternoon near the Capitol. They proceeded down Washington to State, down to North Pearl, over to Clinton and south on Broadway and back to State St. The suffragists wore white hats with yellow cockades and white dresses with yellow sashes. There were women on horseback and in automobiles as well as marchers on foot.

In 1914 the suffragists of Albany decided to mass together for a large parade. On Saturday June 6 about 700 men and women from Albany, its environs and across the State, gathered in the late afternoon near the Capitol. They proceeded down Washington to State, down to North Pearl, over to Clinton and south on Broadway and back to State St. The suffragists wore white hats with yellow cockades and white dresses with yellow sashes. There were women on horseback and in automobiles as well as marchers on foot.

By now a woman named Carrie Chapman Catt was chairwoman of the State Campaign Committee. A windfall dropped into her lap.

By now a woman named Carrie Chapman Catt was chairwoman of the State Campaign Committee. A windfall dropped into her lap. In 1914 Mrs. Frank Leslie, publisher of the wildly popular and profitable “Leslie’s Illustrated Magazine” died and left the bulk of her estate to Catt to promote women’s suffrage . After wrangling with other heirs and attorneys Catt finally received $900,000 in February 1917. Game on. Thousands of dollars went into the New York campaign and other funds were used establish the Leslie Woman Suffrage Commission to promote the cause of suffrage through greater visibility in the public eye and through education. It was called the largest propaganda bureau run by women.

In 1914 Mrs. Frank Leslie, publisher of the wildly popular and profitable “Leslie’s Illustrated Magazine” died and left the bulk of her estate to Catt to promote women’s suffrage . After wrangling with other heirs and attorneys Catt finally received $900,000 in February 1917. Game on. Thousands of dollars went into the New York campaign and other funds were used establish the Leslie Woman Suffrage Commission to promote the cause of suffrage through greater visibility in the public eye and through education. It was called the largest propaganda bureau run by women.