Actress/poet/bohemian Adah Isaacs Menken created a sensation in Albany when she first rode a horse across the stage on June 7, 1861. The attraction was twofold: first, she was performing a traditionally male role in the play, “Mazeppa,” a local favorite since 1833; and second, her character was supposed to be strapped to a horse, naked, and left to die. Adah wasn’t naked, she was covered in diaphanous white cloth – but that was close enough for 19th century thrill seekers.

Her story from a 1964 Knickerbocker News article, by Miriam Biskin:

“At a period when anti-southern feeling ran high, the darling of Albany’s theatre-goers was a New Orleans belle, who wore pink tights from head to foot and who rode to fame strapped to the back of a big black horse. Half of the audience came to marvel at her horsemanship while the other half came to view her daring garb, and neither half left disappointed.

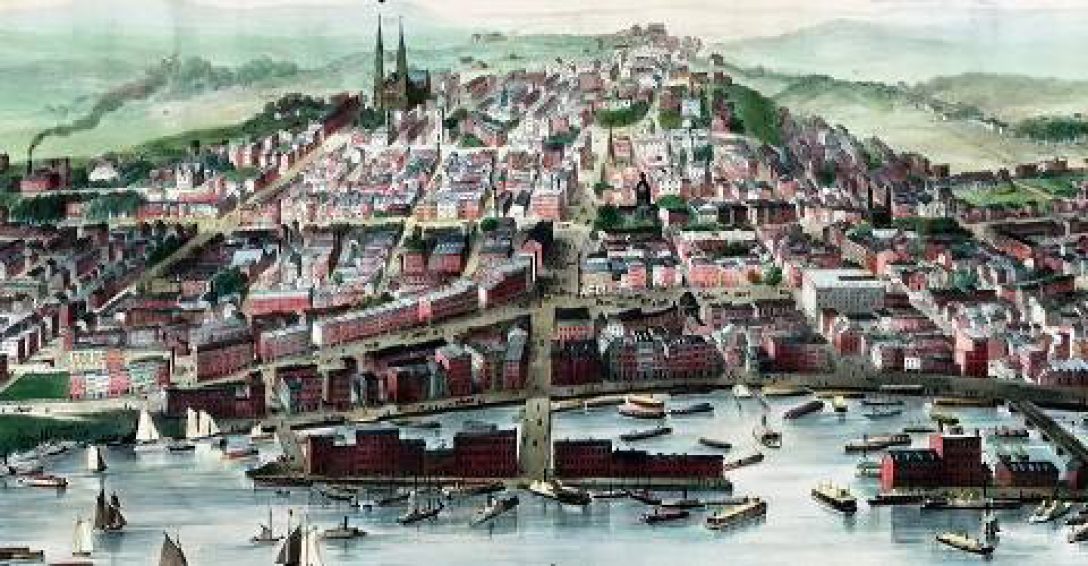

The theatre in which she appeared was located on the west side of Green Street, south of Hamilton. It had been opened to the public on January 18, 1813 in an effort to make a contribution which would “correct the language, refine the taste, ameliorate the heart and enlighten the understanding.”

Such dramas as “The West Indian” and “Fortune’s Frolic” were often shown at box office prices of 50 cents, 75 cents, and $1.00 – whether Miss Menken’s • appearance cause any advance in prices is unrecorded.The theatre was jammed to capacity, however, because by the time Miss Menken appeared in Albany she was already a star in the theatrical world, and her name was synonymous with everything which was daring and exposed.

Extremely buxom, she posed in all sorts of be tasseled portraits in as much undress as the Victorian world would tolerate. Her career had been a series of ups and downs and now that she was on top, she was determined to maintain that position at any price. Born in Milneberg near New Orleans on June 15, 1832, she was named Adah Bertha Theodore. Her father died in a yellow fever epidemic while she was still very young, and her mother remarried a man of some wealth who saw to it that Adah received an excellent education. She learned Latin, Hebrew, Greek and French, and took pleasure in attending the theatre and the opera in New Orleans.

By the time she was 18, she was completely stage-struck, and by the time she was 21, she was appearing with an amateur theatrical group:. She had taken some time off to elope with Isaacs Menken, the scion of a wealthy Cincinnati family. From then on, Menken took over the position of her manager, and Adah was soon appearing in theatres in Shreveport, Vicksburg and Nashville. Wherever she went, she was received with tremendous enthusiasm by a growing host of male admirers. In Dayton, she was feted by the Dayton Home Guard, much to the distress of her jealous husband. He demanded that she leave the stage. She refused and he left. After the divorce, Adah married John Heenan, heavyweight champion (living in WestTroy, NY), who brought her little comfort. Nothing like the docile Menken, he released all sorts of statements vilifying his wife to the papers. Menken added to the furor by issuing her own incendiary statements declaring the initial divorce null and void. A second divorce was soon granted and a new Adah [SENTENCE AND A HALF MISSING, SORRY!]

Adah was a stage-struck girl who wrote excellent poetry in the style of Wait Whitman – religious verse dedicated to Charles Dickens who thanked her profusely for the compliment. The new Adah was a hardheaded publicity seeker who smoked cigars and cropped her hair short in the style of an unkempt urchin. She sought out the bohemians of the day and lived in their free and easy style.

It was at this point that she was offered the role of Prince Mazeppa in Mazeppa or The Wild Horse of Tartary. Cast in the role of the young prince who was strapped naked to a horse and turned loose in the wilderness to die, she was taking a part usually played by a man. And most men were willing to use a dummy substitute for the gallop upstage. But not Menken – she wanted no substitute – and it was her daring which brought crowds into the theatres.

Her tour of New York State was a triumph, and her trip south marred only by an arrest caused by her determination to decorate her dressing room with Confederate flags. In the west, she was welcomed by the miners’ wild adulation and the milder compliments of two young writers, Joaquin Miller and Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain). Clemens, then a reporter for the Virginia City Enterprise, was particularly intrigued by her garb. He described her performance in these terms: “She appeared to have but one garment on – a thin, tight white linen one, of unimportant dimensions; I forget the name of the article, but it is indispensable to infants of tender age.”

He was definitely unimpressed by her acting and horsemanship: “She bends herself back like a bow; she pitches headforemost at the atmosphere like a battering ram; she works her arms and legs and her whole body like a dancing-jack…in a word, without any apparent reason for it, she carries on like a lunatic…if this be grace, then the Menken is eminently graceful.”

Returning from the western tour, Menken embarked for the European capitals and fresh triumphs. The critics deplored the entire production of Mazeppa but this did not deter the ticket-buyers, In Europe, too, she made friends with the great and near-great – Algernon Swinburne., Charles Dickens, Dante Rossetti, Alexander Dumas, pere and others. Between the time of her Albany debut in 1861 and tier Paris appearance in 1864, she had married twice more and borne a son who died in infancy.

Despite personal turmoil, her professional fortunes soared. Paris was at her feet and Menken coats, Menken scarves, Menken collars, and even Menken pantaloons were the rage. Few realized that the glamorous star was ill until she collapsed during rehearsal and died a few weeks later. How long she had been a consumptive no one knew but she was dead at 33 – the flamelike quality that Dickens had called the “world’s delight” extinguished forever. They buried her in a corner of the little Jewish cemetery in Montparnasse, and on her grave stone are the words, “Thou Knowest,” an epitaph she had chosen from Swinburne, the poet who had said of her, “A woman who has such beautiful legs need not discuss poetry.”

Note: Miss Mazeppa is the name of is one of the strippers in “Gypsy”. Homage to Miss Menken’s fame that lingered into the 20th century. “You gotta have a gimmick”.

By Al Quaglieri