When the Battles of Lexington and Concord ended on April 19, 1775 word spread like wildfire through the Colonies. Everyone had been waiting for this, knowing it would come, and not knowing what would happen next. Except that it would be dangerous – 8 colonists died and 9 were wounded on that day.

Yet thousands of men rushed to serve. (Over 350,000 men served in the War over its 7 years.)

There are more than 110 Revolutionary War soldiers buried in Albany Rural Cemetery (and more waiting to be identified).

Some served in the Continental Army, others in state and county militias. Some fought in the local battles we’re all familiar with, like the Oriskany and Saratoga, while others served at Yorktown and Brandywine. Some lived in Albany when they joined the fight, others came to live here after the War. Some were lifelong soldiers, while others were members of minute man companies or the militia, ready to be called up at a moment’s notice.

We’ve put together several brief biographies of those interred at Albany Rural Cemetery that we hope provide you with a better sense of those who fought to forge a new nation.

Daniel Shields

Shields was born in Scotland, but lived in New York City. He enlisted in the Continental Army at the age of 14 (it appears he lied about his age). He served in a NYS regiment under Lafayette at the Battle of Yorktown. (He was discharged with the rank of captain.) Shields received a badge of merit signed by General Washington.

After the War Shields moved between Albany and Schenectady, trying his hand at different jobs. In 1824 Shields and Lafayette had a brief, but fond re-union when Lafayette visited Albany as part of his American tour. Shields’ granddaughter married Leland Stanford (also from Albany), the railroad mogul, politician and founder of Stanford University.

Shields died in 1835, and is interred in Lot 21, Section 11 of the Cemetery.

Goose (Gosen) Van Schaick

Van Schaick was the son of a merchant, who was once mayor of Albany. He’d fought in many battles in the French and Indian War. In 1770 he married a local girl, Maria Ten Broeck; the couple lived on Market St. (now Broadway).

Van Schaick represented his ward on the Albany Committee of Correspondence and would actively serve in the War. He was wounded at the Battle of Ticonderoga in 1777 (in the cheek-the site of a previous wound) and served at the Battle of Monmouth. He was also part of what has come to be known as one of the darker parts of our history, the Sullivan Raids in 1779, in which most of the Indian Nation in the western part of the State was brutally savaged by American troops.

At the end of the War Brevet Brigadier General Goose Van Schaick returned to Albany, still troubled by his cheek wound (which had been determined to be cancerous).

He died on July 4, 1789, age 53. Goose and Maria are buried side by side in Lot 5, Section 3.

Cornelius Van Vechten

Van Vechten was born in 1735, son of a Schagticoke landowner who also served as a firemaster in Albany for a time.

Van Vechten was one of the signers of the constitution of the Albany “Sons of Liberty” in 1766, and 1775 was commissioned Lt. Colonel of the 11th (a/k/a Saratoga) regiment of the Albany County militia. At the time of the Saratoga campaign, the family home at Coveville (Saratoga County) was burned by the advancing British under General Burgoyne. Van Vechten served in the militia until the War ended.

Following the Revolution, Van Vechten served in the State Assembly and, later, as the town clerk in Schaghticoke. He died at age 78 in 1815.

The Van Vechtens were originally buried in the Dutch Reformed section of the State Street Burying Grounds. They were moved to Lot 7, Section 38 at the Cemetery in 1859.

Walter Whitney

Whitney was born in Fairfield, Connecticut in 1760. He served in a unit of the Connecticut artillery as a teenager, from 1777-1779. He subsequently became a school teacher in Connecticut, but moved to outside Albany in the late 1780s (in the towns of Berne and New Scotland) where he also farmed, until his family came into the city in the late 1820s.

He died in 1846 while living at 26 DeWitt Street (now a very small cul-de-sac between Broadway and Erie Blvd).

Whitney’s white marble headstone on the North Ridge is decorated with patriotic emblems – an eagle with a banner bearing the words E PLURIBUS UNUM and a shield rises above a cannon. Look closely alongside the cannon to see crossed swords. Above the eagle are thirteen stars (some are worn and hard to see) for the original thirteen colonies and 76 is carved between the eagle and the cannon.

The Whitney grave can be found in Lot 159, Section 92.

Abraham Eights

Abraham Eights was a second generation American (his grandfather was born in the Netherlands), son of a sea captain, born circa 1745. He settled in Albany in the 1760s, became a sailmaker and lived on Water St. on the Hudson River.

He was one of Albany’s original “Sons of Liberty” in 1766. At the start of War in 1775 he was commissioned a Lt. in the Albany County Militia, but later resigned. He’s found in subsequent records (1777-1779) serving as a private in the Albany County militia on an as needed basis. It appears that he helped the cause with cash and in-kind contributions (ensuring sails were in working order for the sloops that plied the River, and for his next door neighbor Capt. Stewart Dean, who was a commissioned privateer during the War, and with whom he served in the Militia).

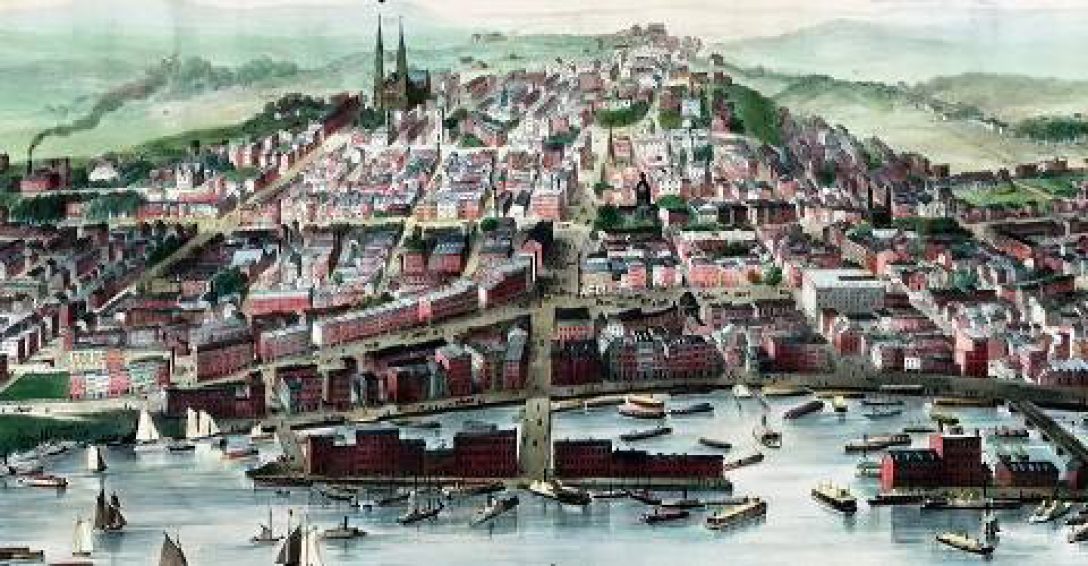

Eights became a wealthy man and in later years was the Dockmaster of Albany. His grandson was James Eights who painted the wonderful watercolors of Albany that show us how the city looked in the early 1800s.

Abraham died in 1820, and is buried in Section 52, Lot 13.*

Josiah Burton

Burton was born Connecticut in 1741. The family then moved just across the border to Amenia in Dutchess County. Historical data suggest that Burton was a silversmith. In May 1775 he was commissioned as a captain in the Dutchess County Militia. It appears he resigned that commission because in 1777 he’s a first lieutenant in an Albany county militia regiment, mustered out of Kinderhook. He moved to Albany in the 1790s and is listed in the Albany County census in the first ward in 1800.

Burton died in 1803 at the age of 61. He’s buried in Section 49, lot 5. *

Benjamin Lattimore – African-American Revolutionary War Soldier

Benjamin Lattimore was born a free man in 1761 in Connecticut. At the outbreak of the Revolutionary War he was living in Ulster County, near New Marlborough, several miles south of Poughkeepsie. Lattimore enlisted (while still a teenager) with the 5th NY Regiment, Continental Army i(n 1776 once Black men were allowed to serve).

A few days later his company was sent to NYC where they took part in the Battle of Manhattan. Later that year he was on duty at Fort Montgomery (on the Hudson, just north of Bear Mountain) when he was captured along with hundreds of other Continentals by the British. Lattimore was re-captured by the Americans in Westchester, and re-joined the Continental Army.

Lattimore’s regiment was also part of the Sullivan Expedition in the western part of NY”, designed to punish the Iroquois for raiding frontier settlements.

By the late 1790s Lattimore and his family moved to Albany. He was licensed by the city as a “cartman” (authorized to haul cargo through the city streets). By about 1810 Lattimore also owned a grocery store, ad began to accumulate real estate.

Throughout the rest of his life Lattimore was active in advancing the conditions of African- Americans in Albany. He was part of a group that established the first “Albany School for Educating People of Color” in the ealry 1800s, was founding member of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church and was chairman of the Albany committee to celebrate the abolition of slavery in New York State in 1827.

He died in 1838 at the age of 78 and was buried in the AME cemetery. Records indicate that his remains were moved to Albany Rural Cemetery, but his headstone has gone missing.

*Abraham Eights’ daughter Catherine married John Burton, son of Josiah Burton in the 1790s (my 3rd great grandparents).

Thanks to Paula Lemire, Historian at the. Historic Albany Rural Cemetery for much of this information and to Stefan Bielinski, for the information he has discovered about Benjamin Lattimore in his Colonial Albany Project http://exhibitions.nysm.nysed.gov//albany/welcome.html

Copyright 2021 Julie O’Connor

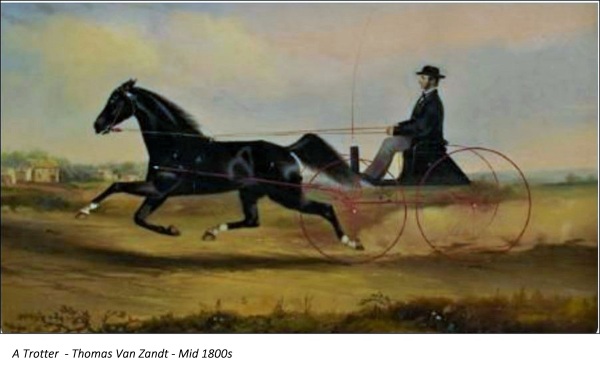

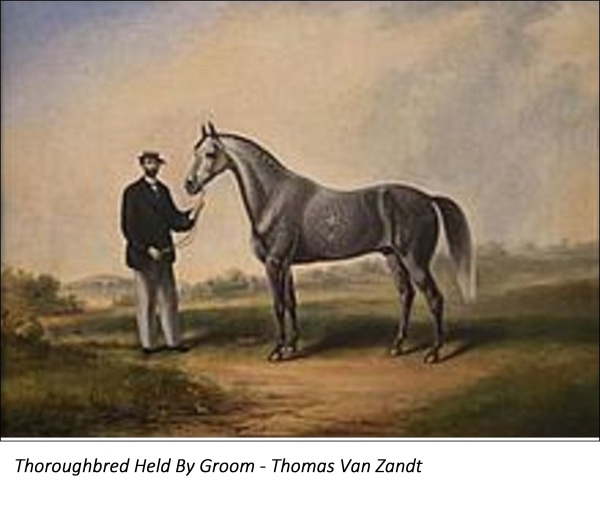

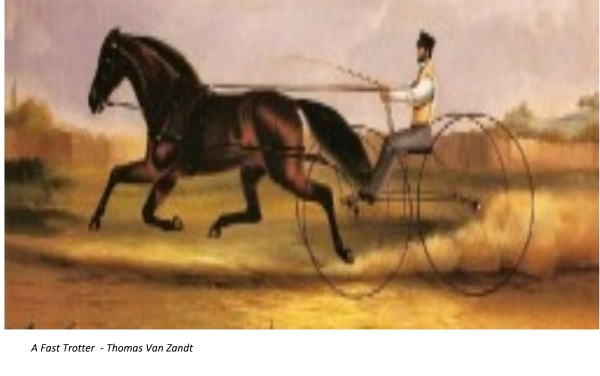

Kirby was born in 1814 and by time he was 30, in 1844, identified himself as a painter in the city directory. At that time he was living on State St. between Lark and Dove. He sounds like a young man who was fairly confident in his talent and his ability to make a living through his art. The confidence was not misplaced; he was very successful over 40 years. He specialized in horses and farm animals. The area outside Albany was still rural and scattered with hundreds of farm in the surrounding counties,. If you were a fairly well-to-do farmer, you would have the well-known painter Kirby Van Zandt paint your prize winning chicken or bull. Kirby also established himself as a horse-and-carriage painter catering to Albany’s wealthier citizens, like Erastus Corning and Kirby’s brother-in-law, Judge Van Aernum (the painting of the Judge and his sleigh is in the permanent collection of the Albany Institute of History and Art). In later years he specialized in horses and spent time in Saratoga at the horse tracks.

Kirby was born in 1814 and by time he was 30, in 1844, identified himself as a painter in the city directory. At that time he was living on State St. between Lark and Dove. He sounds like a young man who was fairly confident in his talent and his ability to make a living through his art. The confidence was not misplaced; he was very successful over 40 years. He specialized in horses and farm animals. The area outside Albany was still rural and scattered with hundreds of farm in the surrounding counties,. If you were a fairly well-to-do farmer, you would have the well-known painter Kirby Van Zandt paint your prize winning chicken or bull. Kirby also established himself as a horse-and-carriage painter catering to Albany’s wealthier citizens, like Erastus Corning and Kirby’s brother-in-law, Judge Van Aernum (the painting of the Judge and his sleigh is in the permanent collection of the Albany Institute of History and Art). In later years he specialized in horses and spent time in Saratoga at the horse tracks.

The Van Zandt paintings are referred to as “folk art”, but that isn’t meant to diminish the quality of the paintings. It’s a term that just describes their style. The Metropolitan Museum says these 19th century “ (folk)artists worked principally in the Northeast… Almost all of them favored strong colors, broad and direct application of paint, patterned surfaces, generalized light, skewed scale and proportion, and conspicuous modeling. Most developed compositional formulas that allowed them to work quickly, with limited materials and in makeshift studios.” This describes Van Zandt, moving from farm to farm and painting livestock and chickens in barns. In an era when photography was still a new thing, Van Zandt paintings were widely known in this area as way to preserve the image of your favorite animal.

The Van Zandt paintings are referred to as “folk art”, but that isn’t meant to diminish the quality of the paintings. It’s a term that just describes their style. The Metropolitan Museum says these 19th century “ (folk)artists worked principally in the Northeast… Almost all of them favored strong colors, broad and direct application of paint, patterned surfaces, generalized light, skewed scale and proportion, and conspicuous modeling. Most developed compositional formulas that allowed them to work quickly, with limited materials and in makeshift studios.” This describes Van Zandt, moving from farm to farm and painting livestock and chickens in barns. In an era when photography was still a new thing, Van Zandt paintings were widely known in this area as way to preserve the image of your favorite animal. Stanford, who loved horse and horse racing (the shared passion with Van Zandt) believed that at a horse ran all four legs left the ground and at some point it was suspended in the air. Stanford wanted Muybridge to capture this moment in the horse’s stride, an instance imperceptible to the naked eye. Muybridge took a series of photos. The plate itself was fuzzy and unsuitable for publication, so it was left to Van Zandt to strengthen the image. He reproduced the image twice, first as drawing of “crayon and ink wash” dated September 16, 1876, and again as the finished canvas in 1878.

Stanford, who loved horse and horse racing (the shared passion with Van Zandt) believed that at a horse ran all four legs left the ground and at some point it was suspended in the air. Stanford wanted Muybridge to capture this moment in the horse’s stride, an instance imperceptible to the naked eye. Muybridge took a series of photos. The plate itself was fuzzy and unsuitable for publication, so it was left to Van Zandt to strengthen the image. He reproduced the image twice, first as drawing of “crayon and ink wash” dated September 16, 1876, and again as the finished canvas in 1878.

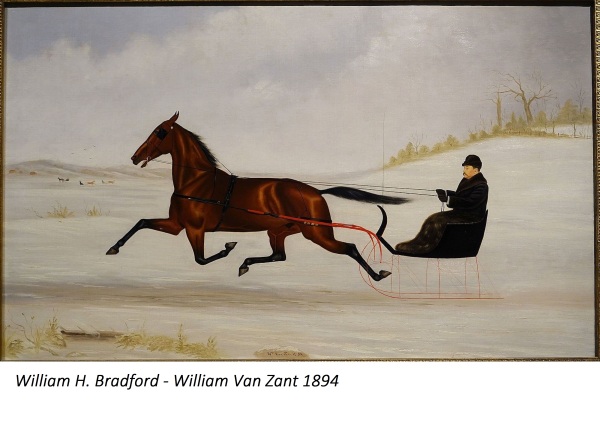

This brings us to his son, William who followed in his father’s footsteps. William was born in 1867 while the family lived in Albany. He had his father’s talent and his love of horse and horse racing. William was actually a “starter” for the Saratoga races and a member of Albany Driving Club. (The Driving Club met at Woodlawn Park – where Albany Academy for Boys is currently located and held trotting horse races.) In addition to painting, William held several jobs, including Albany City vital statistic registrar and then assistant superintendent for art in the Albany public schools. He lived at the family farm in New Scotland, then in the city at several uptown locations and then spent the last 20 or so years in Guilderland. He passed away in 1942.

This brings us to his son, William who followed in his father’s footsteps. William was born in 1867 while the family lived in Albany. He had his father’s talent and his love of horse and horse racing. William was actually a “starter” for the Saratoga races and a member of Albany Driving Club. (The Driving Club met at Woodlawn Park – where Albany Academy for Boys is currently located and held trotting horse races.) In addition to painting, William held several jobs, including Albany City vital statistic registrar and then assistant superintendent for art in the Albany public schools. He lived at the family farm in New Scotland, then in the city at several uptown locations and then spent the last 20 or so years in Guilderland. He passed away in 1942.