The article below tells the story of the establishment of a free Black community in Albany, New York. The Albany African Society, lead by a Black Revolutionary War soldier, Benjamin Lattimore Sr., who could neither read or write, his teenage son, Benjamin Lattimore Jr. and about a dozen other free Black men built a school and a church in the city’s South End in 1812. It was a remarkable feat, and there appears to have been nowhere else in the new nation where free people of color managed to succeed at such an endeavor.

This story has never been told before, and I could not have done the research without the help of these women Jessica Fisher Neidl – Museum Editor, New York State Museum; Maura Cavanaugh – Archivist, Albany Hall of Records; Dr. Jennifer Thompson Burns – Dept. of Africana Studies, University at Albany: Lorie Wies – Librarian Saratoga Springs Public Library; Paula Lemire -Historian, Albany Rural Cemetery.

It builds on work by Stefan Bielinski (New York State Education Dept.) and an independent historian, John Wolcott.

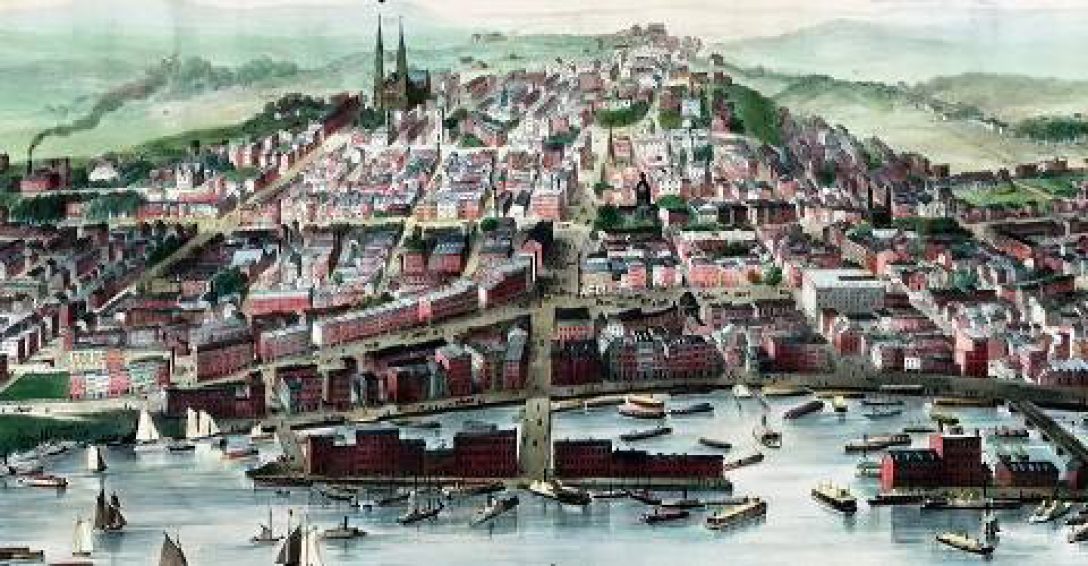

Albany at the turn of the 19th Century

Despite what must have seemed almost insurmountable obstacles free African Americans in the city of Albany established what would become a thriving community in the first two decades of the 1800s. This was during the time in New York State when slavery was legal, and there were still over 250 enslaved people in the city. Similar activities were going on in other Northern cities – Boston, New York City and Philadelphia which had much larger populations of free people, and slavery was no longer as entrenched as it was in Albany. Slavery was not only an economic proposition for what was still mostly Dutch Albany – it had become almost a cultural tradition.

The first Federal census of 1790 begins to tells part of the history. Albany had a population just shy of 3,500. An astonishing 16% (572) of that population was enslaved, compared to the 6.3% across all of New York State. Only 26 free persons of color were counted in the city .

Slavery in Albany

Many people think of slavery as just something that happened in the South, but it was very much a northern institution, especially in Albany. Descendants of old Dutch settler families were reluctant to abandon slavery into the early part of the 1800s.

The first enslaved men from Angola were brought to Fort Orange (Albany) in 1626, only 2 years after it was first settled. They were the property of the Dutch West India Company, owner of the New Netherland Colony. The practice of enslavement continued. In 1657 when Peter Stuyvesant, the Governor of the Colony, requested more settlers from the Company the directors told him to acquire more enslaved people to meet the demand for labor.

After the British took over the Colony in the 1660s the slave trade increased exponentially. The English began developing more stringent rules than the Dutch governing the enslaved; forbidding gatherings of Africans, limits on travel, etc. Slavery continued in New York State until the Revolutionary War and beyond. The number of enslaved people in the State actually increased after the War, as did the number of individuals who owned enslaved people.

Slavery was the economic engine of New York State in the 1700s. Enslaved people were valuable capital and personal property. As chattel they were bought, sold and inherited – like the family silver. Families were separated; husbands from wives and their families; mothers from children. Women had no agency over their bodies. By the 1850 Albany census, more often than not you can find the word “mulatto” (not Black) next to the names of persons of color -the legacy of unwilling unions.

Free People of Color in Albany

Conditions began to change to slowly. In 1799, under Governor John Jay (founder of the New York State Manumission Society) the New York State Legislature enacted the ‘Gradual Abolition Act”. The Act required that all children born to enslaved women be freed, but far into the future. Males would be freed when they reached 28 years of age; females age 25. Practically speaking there was no real impact of the legislation. Children could still be separated from their mothers – sold or rented out. But the Act did serve as a catalyst for some owners to free those they enslaved. (But not John Jay. While serving as governor and living on State St. in Albany he owned five enslaved people.)

Finally, by the 1810 federal census the number of enslaved people in Albany was reduced by half, to 251. By then the city’s population had tripled to 10,762. Albany was moving from a sleepy, very Dutch frontier town to a thriving and vibrant metropolis. It was the 10th largest city in United States. The number of free people of color had grown to 501, an increase of 1800% in 20 years. For the first time Albany’s free African population outnumbered the enslaved population.

But it was a confusing time and must have been difficult to navigate for free people of color. Some enslaved people were freed outright. Some members of families were freed, while others remained enslaved. Often owners required that those they enslaved purchase their freedom or the freedom of their family members. White households in the 1810 census often included both free people of color and enslaved people. Different owners had often owned different family members; some were freed, but others not. Intact free family units with parents and all the children were a rarity. Albany census data identifies a number of female-headed Black households; women and children who had been manumitted. One of these women Silva (Sylvia), had been enslaved by Philip Schuyler. On his death in 1804 his executors freed her and her three children – she spent the rest of her years in Albany earning her living as a fortune teller.

Some people were freed, but with conditions. One Albany woman was required to return to her previous owner every Spring to help with house cleaning. Archival records identify promises to free enslaved people upon the death of the owner. Other records indicate the sale of an enslaved person for a period of time (e.g., five or seven years) with a promise of freedom at the end of that term.

Some Black families spent years trying to acquire freedom for all family members, often scattered across New York State. Manumission records preserved in the Albany County Archives are often are heart-breaking, as are newspaper ads that continued to announce “Negro” men, women (mostly referred to as “wenches”) and children for sale.

And yet the free African American community in Albany continued to push forward.

Albany’s population began to grow after it was selected as the capital of New York State in 1797. It increased exponentially after Robert Fulton sailed his steamboat up the Hudson River from New York City. A number of turnpikes were built improving access to all areas of the New York State from Albany. The city became a transportation hub of the Northeast. Free Black, as well as white, migration into the city followed.

Free people of color found employment on the waterfront, and as laborers building much needed new housing stock as the city grew to accommodate the population spike. Many worked in livery stables serving the multiple stagecoach lines that ran from Albany to all points. Others worked as waiters, cooks and laundresses for the hotels, taverns, inns and porterhouses that sprang up to serve travelers coming through by stage and new steamboat lines. A few were skilled artisans– barbers, a blacksmith, a shoemaker. Albany (unlike New York City) licensed Black men as cartmen (think truck drivers today) and city sweeps.

A Growing Black Middle Class

A free Black community began to emerge, probably comprised of about 50-60 households. There were even a number of Black property owners.

They began to create their own institutions to meet their needs as had the much larger free Black communities in New York City, Boston, and Philadelphia. These Black Albanians understood the need to create their own social and religious spaces apart from the white community.

The Albany African Society

A small group of men came forward to take on this task, establishing the Albany African Society, possibly as early as 1807, but clearly by 1811.

The Albany Society was modeled on the New York City African Society for Mutual Relief, founded in 1806. The group pooled funds among members to help with burial costs and aid widows and children. But the Albany Society had broader goals. In addition to mutual relief, it focused on the establishment of an African School and an African church. Members of the Black community understood the critical need to provide an education for their children.

Albany’s African Society was contemplating something that would take an heroic effort. Although the number of free Blacks in Albany was much smaller than the free Black populations in the cities of Boston and New York, they were determined to create their own Black identity and culture.

Ben Lattimore Sr. emerged as the leader of the Society. In 1811 Lattimore was about 50, the father of a teenage son, Benjamin Jr., from a first marriage. There were also 3 young children – William – age 7; Betsey – age 6, and Mary – age 4 from his second marriage in 1803 to a local woman named Dinah. She had been enslaved by a well-respected Albany doctor, Wilhelm Mancius. We know little about the marriage; it’s quite possible Lattimore bought Dinah’s freedom.

Lattimore was born free in Weathersfield, CT. and grew up in Ulster County, where his father Benoni owned Lattimore’s Ferry across the Hudson River at the southern end of the county. He was a Revolutionary War veteran; enlisted when he was about 17 years old, and served 4 years in the Continental Army. At one point he had been taken prisoner by the British, but managed to escape back to American lines. He arrived in Albany from Poughkeepsie with his young son around 1794. It’s probable he came to Albany (which he would have known from his War service), where he had a kinsman for a fresh start and greater opportunity.

By 1798 he purchased property at 9 Plain St., off South Pearl St. (then known as Washington St.) close to State St. for which he paid £170. (This was at a time when the average income for a worker was about £60.) In 1799 he became a member of the Presbyterian Church which appears to have been more inclined to welcome Black congregants than other churches in the Albany. It was the church that was most often attended by the white middle class of shopkeepers and skilled workers, and newcomers to the city.

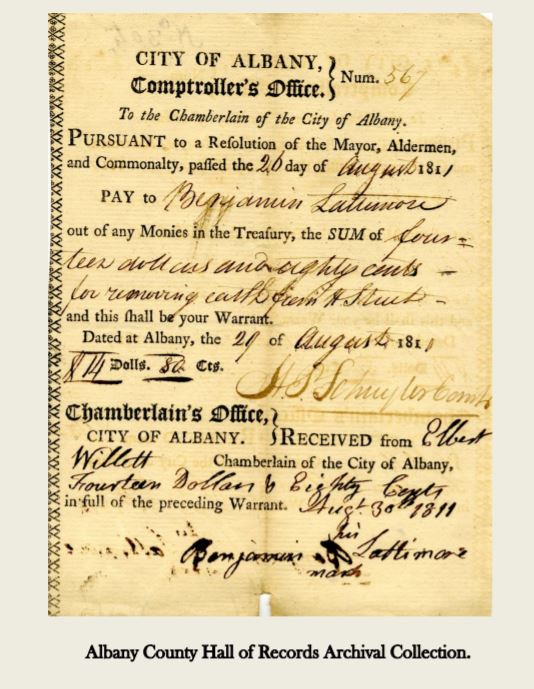

In 1811 Lattimore was a cartman licensed by the city. The Albany County Hall of Records has a copy of a bill paid to him for services rendered by the City in the amount of $14.80 (about $300 in today’s money).

The role of cartmen was critical to commerce and the life of the city. They were the only individuals permitted to move goods through the streets. Everyone, Black and white, knew the cartmen. Only they could move your “stuff”, whether a featherbed or cargo from a newly docked ship. A responsible cartman, who didn’t price gouge, and delivered your goods in a timely manner, undamaged, after having navigated steep Albany hills and three large creeks (the Beaverkill, the Ruttenkill and the Foxenkill) was a man who was well-known and well-respected by both the Black and white community.

The 1815 city directory and subsequent directories include the names of cartmen (and their cartman number) along with other important city officials. Their inclusion is a clear indication of the importance of the cartmen in the eyes of city government and the public at large.

Little else is known about Lattimore who would become the driving force in Albany’s Black community for three more decades, except for several scraps gleaned from old documents. In an 1820 court deposition attesting to his free status Lattimore was described as “tall, thin and spare, with a light complexion and hazel eyes”. If he looked anything like his son (we’ve seen a picture of him at about that age), he had kind and intelligent eyes, with a bit of twinkle and a wry smile. The same deposition describes Lattimore as a man of “irreproachable character of integrity and uprightness.”

In 1811 Lattimore purchased a lot from Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, the daughter of General Philip Schuyler and widow of Alexander Hamilton for $400. It was her inheritance portion of the General’s estate, part of the farmland that had surrounded the family Mansion. The property was narrow (34 ft.) and long (135 ft.), located on Malcolm St. (now Broad St.), and ran through to Washington St. (now South Pearl St.)

Not only did Mrs. Hamilton sell a parcel of land to Ben Lattimore, Sr, but there were two other Black buyers. Prince Schermerhorn and Capt. Francs March purchased property from Mrs. Hamilton the same day as Ben Lattimore Sr.

Obtaining an education for his children was probably of upmost importance for Lattimore. Five documents survive ((a deed, cartman’s bill, his deposition as a free man, pension application and will) survive. Only one ( his pension application) bears his signature; the rest have only his “mark”. We conclude he was illiterate and must have thought it was critical that his children possess the ability to read and write. (It probable that his oldest son Ben Jr. learned how to read and write from a Mrs. Jones who owned a small school on Plain St. near the Lattimore home in the early 1800s.)

Prince Schermerhorn was the son of a white landowner, Samuel Schermerhorn, from a prominent old Dutch Settler family in Kinderhook, Columbia County. An attestation in Albany court in 1821 indicates “he was born free and never has been a slave”.

Capt. Francis March was in his late 30s in 1810. He had been a free man for at least 20 years in 1811 (based on the 1790 census), and previously lived in the town of Watervliet (north of the Albany city limit) with his wife Cornelia. In multiple city directories he’s listed as living at 217 South Pearl St. (the property he purchased from Mrs. Hamilton), and identified as a skipper.

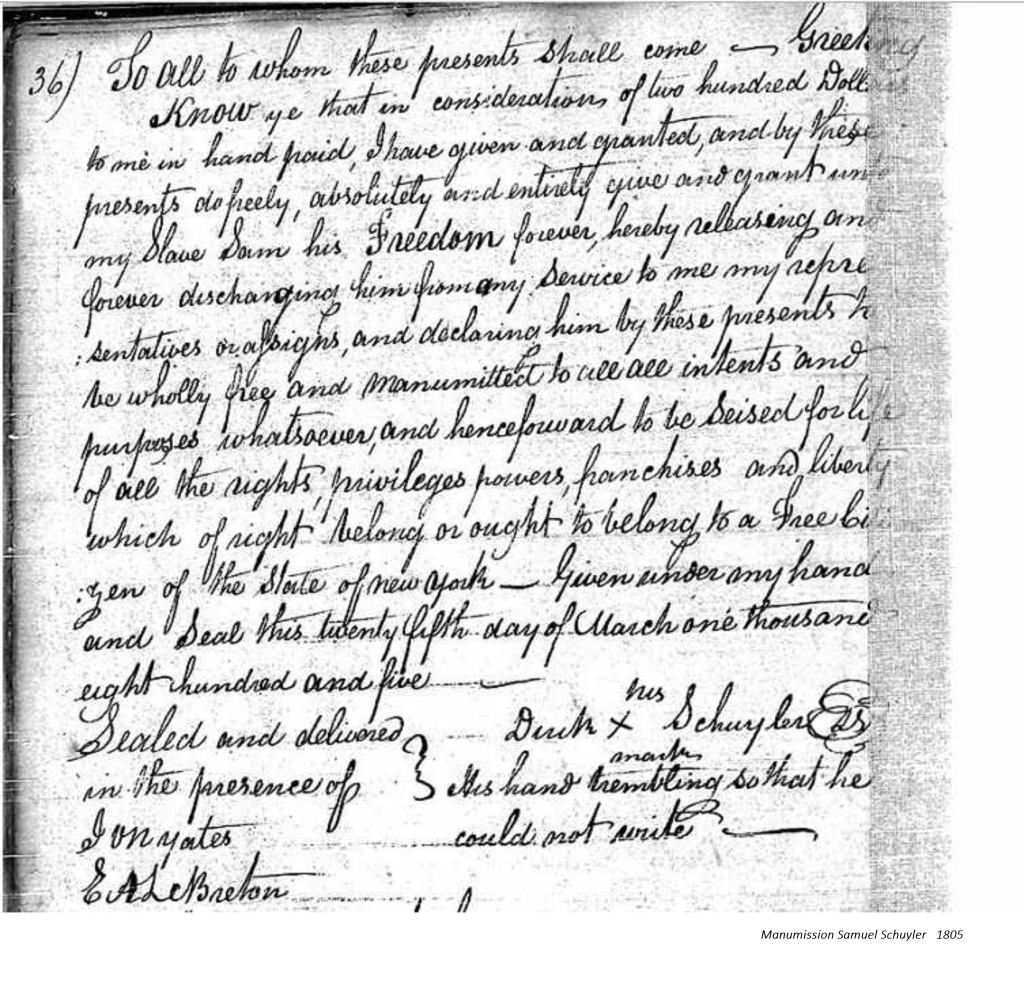

Capt. Samuel Schuyler was also in his 30s, and lived at on South Pearl St., at number 204, which he purchased in 1809, possibly from an earlier sale by Mrs. Hamilton. (The last of the Albany land she appears to have inherited- 32 lots – was sold at auction in 1814.) Schuyler had only recently been freed by Dirck Schuyler (presumed to be his white father) in 1805.

Manumission records indicate he purchased his freedom for $200. Schuyler would go on to become a well-known Hudson River ship captain, and owner of other property in Albany. Schuyler married in 1805 immediately after his manumission and had three children by 1811. Schuyler also owned land on Bassett St. close to River docks. Schuyler and Francis March were the best of friends, and lived in the same block of South Pearl St. between Westerlo St. and South Ferry St. for decades. Schuyler’s first child was named Richard March Schuyler in honor of Francis March.

Thomas Lattimore is presumed to be a relative (perhaps a cousin) of Benjamin Lattimore. He married a local free Albany woman, Margaret Foot, and they were both received members of the Presbyterian Church. He appears to have been the owner of property on Albany’s Pine St. in the early 1800s (based on tax assessment record). In 1811 Thomas had two sons, John Hodge (age 11) and Robert (age 9), both baptized in the Presbyterian Church. It is quite possible he worked as a stone cutter for John Hodge (after whom Thomas named his first son), originally from New Marlboro, in Ulster County, where Benjamin Lattimore grew up. John Hodge was an elder in the Presbyterian Church.

Francis Jacobs was born free in Brooklyn in 1758. He was a Revolutionary War veteran, but one who served in a remarkable capacity. In late 1777 he joined the military household of General Washington as a waiter and sometimes scout; he served in the General until at least 1783. Upon his separation from Washington’s service the General provided Jacobs with a hand-written letter of recommendation.

In the 1813 Albany directory Jacobs was identified as living at 24 North Pearl St. as a “sweep master”. (A newspaper ad in the same year also identifies Jacobs as a dealer in second hand clothing.) We know little else about Jacobs except that he too was in his early 50’s and probably had 5 children. (In later years he moved to Waterford where he was a lock keeper for the Erie Canal.)

Thomas Elcock (also known as Olcott, Ellicott, Alcock, Allicott, Ollicott, etc.) was age 42 in 1811. The first city directory in 1813 identified Ellicock living at 39 Columbia St., The 1815 directory identified him as a cartman, the same occupation as Benjamin Lattimore Sr, Elcock had been one of many people enslaved by the wealthy merchant Abraham Lansing, from one of the most important old Dutch Albany families. He was freed in 1804 by Lansing, but it is thought that the rest of his family – wife and children – were owned by Stephen Lush, Lansing’s wealthy neighbor. (Coincidently, Lush served with Benjamin Lattimore at Fort Montgomery during the Revolutionary War, and both were taken prisoner by the British.) It’s probable Elcock purchased the freedom of his wife and most of children between 1806 and 1810. Manumission records indicate that Elcock finally bought the freedom of his 18-year-old son Thomas Jr. from Stephen Lush in 1818 for $130.

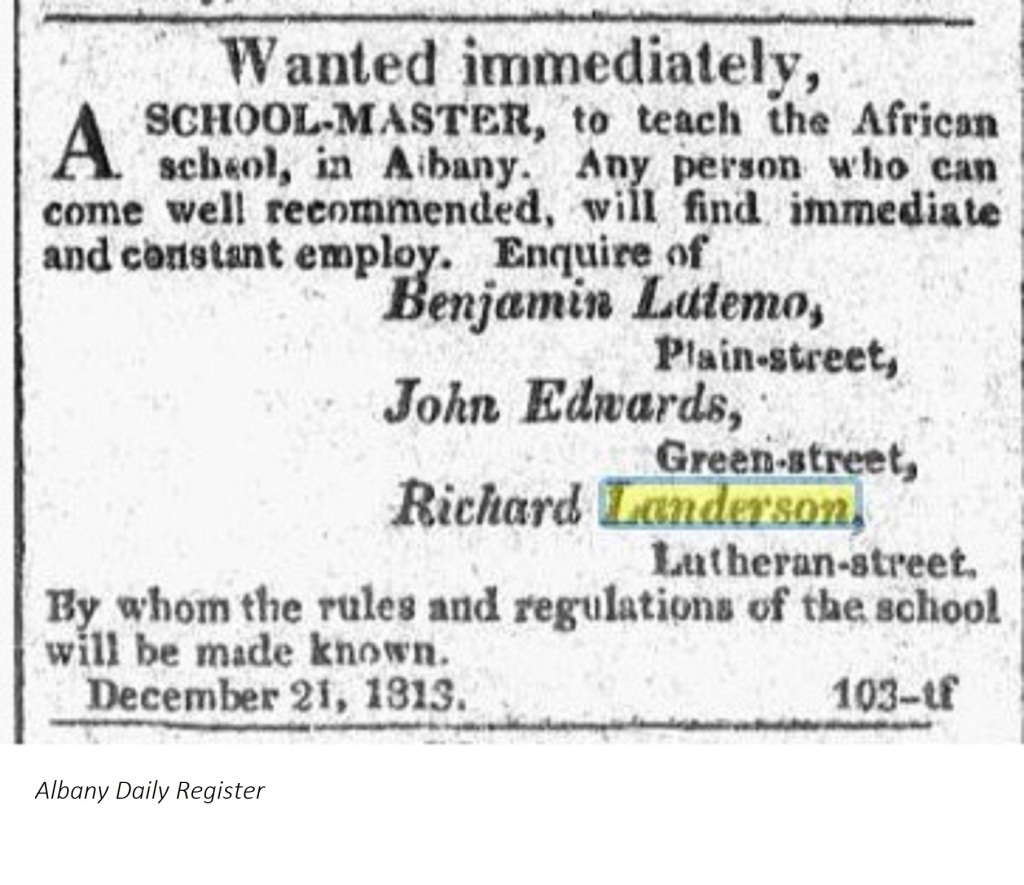

Richard Landerson was 24 in 1811. He was freed in 1810 by Ephraim Starr, a wealthy attorney who moved to Albany from Connecticut several years prior. Manumission records indicate his freedom was based on an agreement with Starr in May, 1808. Landerson was to pay Starr $200 with interest for the term of four years and was not to “loose any time in the afore-mentioned term of four years, but shall labor and do his duty faithfully and for such persons and in such places as they can mutually agree”. Landerson agreed to behave with “prudence and propriety”, and to allow Starr his “wages, unless for clothes, to an amount not exceeding $40 per year”, and to pay him $200 with interest as much sooner than four years as possible. Landerson fulfilled his end of the bargain in 27 months and was freed in August, 1810. In 1813 he was living on Lutheran St., which was located on the west side of South Pearl St. up the hill.

Samuel Edge was a shoemaker on Chapel St. (1815 city directory) who had been born enslaved in St. Croix in the Virgin Islands in 1790. In 1811 he was about 22 years old.

John Edwards was born in Boston. In an 1819 court deposition regarding his status he stated he had been free since the mid-1790s. Edwards was a well-known barber on Green St. who advertised his services in the local newspaper (something rarely done by Black men). In his deposition he is described as 5’ 9” with a dark complexion.

Baltus Hugemon (aka Hugenor,Hugener, Hugoner) carried the name of a well-known old Dutch settler family from New York City, Albany and the Hudson Valley in which he or members of his family were probably enslaved at some point. He appears to have been a member of a family that had been free people of color for some time. There are several free Blacks with that surname in the early part of 19th century in Albany, including a Dina Hogener identified as a property owner in the 1805 tax assessment. Hugemon was listed as a property owner in the 1801 Albany tax assessment. He’s identified in the 1817 city directory as living in the Arbor Hill section of the city.

John Williams was probably a barber. In an 1811 court deposition in which he certified his status he stated he was 36 years old and had been born free. It’s possible that he was married to Catherine, granddaughter of Dinah Jackson. (A John Williams is identified in Dinah Jackson’s 1818 will.) Dinah, who lived on Maiden Lane, was one of the earliest known Black property owners in the city in 1779.

Little is known about John Depeyster. But like much of the Black population in Albany at the time with Huguenot and Dutch surnames, his family was quite likely enslaved by one of the old Albany settler families at some point. The DePeysters were a large and extensive family who intermarried with the Van Cortlandts, Livingstons and Schuylers, and owned large swaths of property from New York City, up through the Hudson Valley to Albany.

Richard Thompson owned a grocery store at 22 Fox St. (i815 city directory). It’s probable that Peggy Thompson, a free woman of color who joined the Presbyterian Church in 1807, was his wife. They had a son, Richard Jr. who was probably about 5 years old in 1811.

The Common Council Gets Involved

Varying attitudes of the white community contributed to the need for Africans in Albany to navigate that world carefully. The actions of the Albany Common Council at this time make this very clear. There was no way for the Black community to predict what it would allow for the “colored” residents of the city,. For example, unlike New York City’s municipal government, Albany permitted Black men to be licensed cartmen, a profession that allowed them to accumulate wealth. But there were other decisions by the Council that demonstrate endemic racism.

It appears that establishment of an African School was on the minds of both Black and white citizens of Albany for some time. In the Albany County Hall of Records there is a fragment of an 1810 letter (unknown author) addressed to the Albany Common Council. The letter references the intent of the Black community dating back to 1807 to establish a school, and scolds the Common Council for failing to provide assistance in this endeavor.

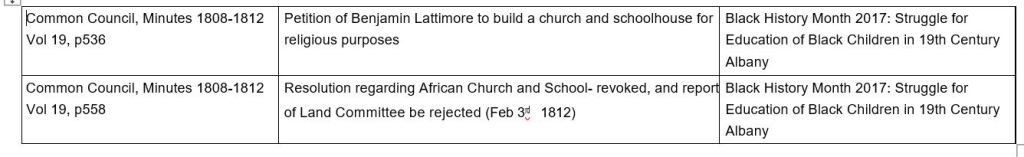

The minutes of the Common Council reveal the true thinking of many of the members of the Council. At some point, probably in Fall, 1811, the Albany Common Council received a petition from Benjamin Lattimore Sr. and other officers of the Society requesting the city allocate a lot to build a church and school house.

On December 9, 1811 the Land Committee of the Council submitted a report recommending “… that a deed be executed for that purpose for a lot on the west side of Elk Street west of the public square of sufficient size to answer the objects contemplated by the petitioners, and that until the said Society is incorporated the deed be executed to James Van Ingen Esq. as trustee for the said petitioners who agree to accept the same as such. The Committee are however of the opinion that a covenant be inserted in the said deed that the said lot shall revert back to the corporation whenever the same shall be appropriated to any other use than that set forth in the said petition.” That recommendation was approved by the Council.

(James Van Ingen was the attorney who acted on behalf of Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton when she sold land to Lattimore, Sr., Schermerhorn and March earlier that year. And yet in those paradoxical times Van Ingen is identified as owning two enslaved persons in the 1810 census.)

But barely two months later the Common Council rejected the report of the Land Committee and revoked the deal. On February 3, 1812 the Council minutes read, “Resolved that the resolution of the 9th of December last approving of a report of the Land Committee granting a lot of land for certain Africans and people of Color for religious purposes be revoked and that the said report of the Land Committee be rejected.” No explanation for this action is found in surviving Council documents or newspapers.

Perseverance

The revocation of the land grant must have been a shock to the Society. But they persevered, and came up with another plan. Benjamin Lattimore was by now a force to be reckoned with. He sold the property he purchased from Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton in April, 1811 to his son, Benjamin Lattimore Jr. for $400, the amount he had paid for the property, In June 1812, Benjamin Jr. then sold the land to a group of eight men who were trustees of the African Society. Lattimore Jr. held the mortgage.

Financing the School and the Church.

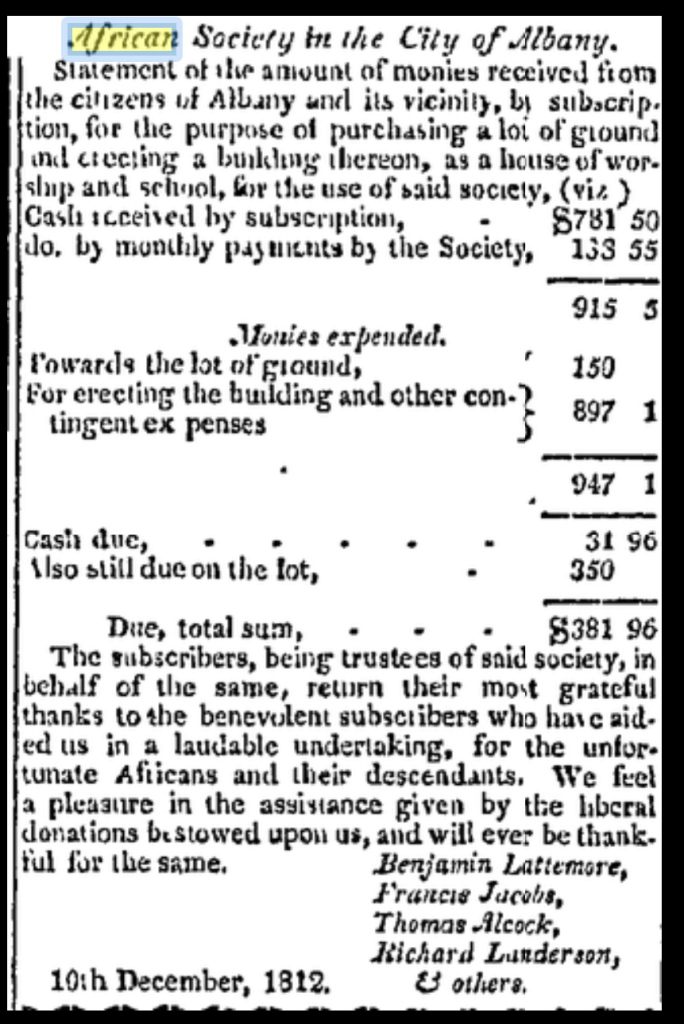

Then the African Society went about raising money for the school and the church. Within six months, on December 10, 1812, there appeared an announcement in the Albany Gazette to the citizens of Albany from the Trustees of the African Society on progress to date. The announcement was signed by “Benjamin Lattimore, Francis Jacobs, Thomas Alcock, Richard Landerson & others”.

It’s a statement of the status and accounting of the Society’s fundraising for the school and church. A total of $915 had been raised. While 14% of the funding appears to have been provided by the trustees and other members of the Society, an astonishing 86% (over $700) had been contributed by the citizens of Albany. Most of the funding came from the white community. Another Albany paradox.

That was a lot of money, from a city in which there were probably 200 individuals still enslaved. But it speaks to the growing dichotomy in Albany. “Yankees” had come flooding in from Massachusetts (where slavery had ended before 1790) and other New England states. Some religious denominations were slowly and tentatively pushing towards total abolition of slavery. There was also a growing understanding about the need for education of Black children and adults, if only as a “public good”, benefitting the entire community.

The funding of an African school in Albany by the white community is remarkable. We can find no other instance in which the charitable impulses of a city were harnessed in this way for the benefit of its Black population. And it leaves us wondering about the relationships between the Trustees of the African Society and members of the white community. Were there several large donors among the wealthy of Albany? Did money come from churches? How many individual donors contributed? It’s likely we may never know the answers.

The announcement read:

“The subscribers, being trustees of said society, on behalf of the same, return their most grateful thanks to the benevolent subscribers who have sided with us in this laudable undertaking, for the unfortunate Africans and their descendants. We feel a pleasure in the assistance given by the liberal donations bestowed upon us, and will ever be thankful for the same”. It further indicated that most of the necessary funds for the building had been raised, and that the Society was making good progress, although there were some debts remaining, mostly for the land cost.

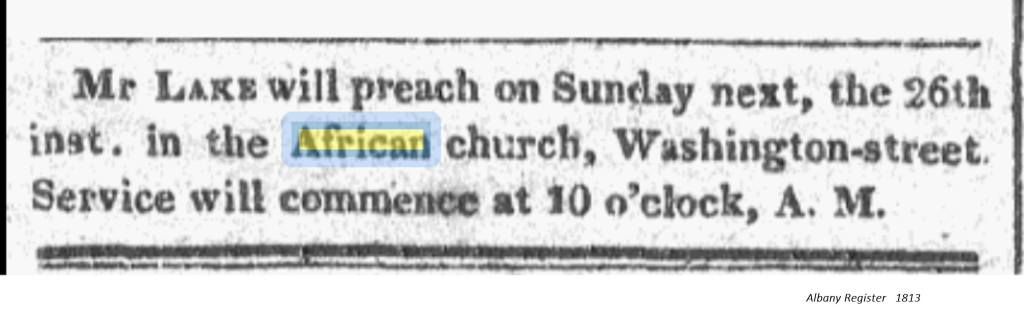

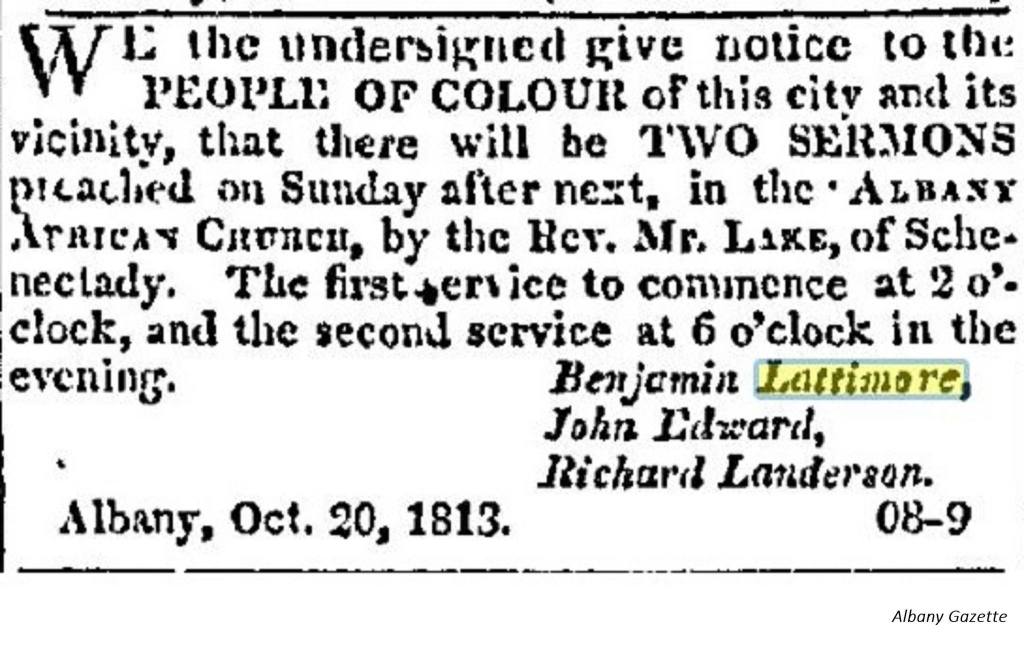

Ten months later in October,1813 there was another newspaper ad (signed by Benjamin Lattimore, John Edwards and Richard Landerson) addressing “People of Coulour” . It announced that two sermons would be preached by the Rev. Mr. Lake from Schenectady in the Albany African Church on Sunday October 31, 1813.

By December, 1813 an advertisement was placed in the Albany Register by the same men (Lattimore, Edwards and Landerson) seeking a schoolmaster to teach in the African School in Albany. It stated, “Any person who can come well recommended will find immediate and constant employment”.

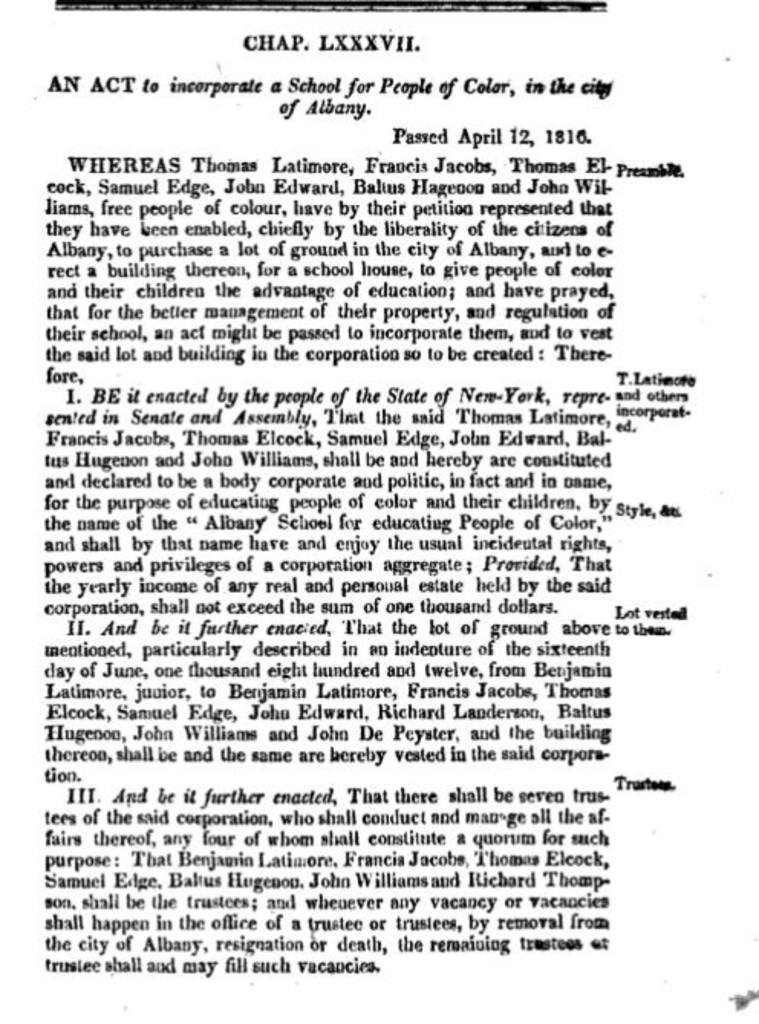

School Incorporation by New York State Legislature

Nothing more is heard about the school until New York State legislation was enacted on April 12, 1816 permitting incorporation of the school. The bill was introduced in the New York Senate by Federalist Abraham Van Vechten who had previously been New York State Attorney General. (During that time one of his clerks had been a young man of Jewish and African heritage. Moses Simon, the first Black graduate of Yale Law School.)

The legislation identified Thomas Latimore (sic), Francis Jacobs, Thomas Elcock (sic), Samuel Edge, Baltus Hagemon, and John Williams, free people of color, as petitioners for New York State approval of the incorporation of a school for people of color in Albany. The legislation stated, “.. they have been enabled chiefly by the liberality of the citizens of Albany, to purchase a lot of ground in the city of Albany, and to erect a building therein, for a school house, to give people of color and their children the advantage of education, and have prayed, that for the better management of their property, and regulation of their school, an act might be passed to incorporate them, and to vest in the said lot and building in the corporation to be created ..” (Reading between the lines it appears that the management of the school had not gone smoothly, probably for lack of resources, and there was the hope that formal New York State recognition might facilitate the Society’s ability to continue to raise funds.)

The legislation further indicated that the men identified above (Latimore, Jacobs, Elcock, Edwards, Hagemon and Williams) were to be incorporated for the purpose of education of people of color and their children as the “Albany School for Educating People of Color”( as long as the real and personal estate income of the corporation did not exceed $1,000 annually).

The trustees of the school are identified in the statute aas Benjamin Latimore Sr., Francis Jacobs, Thomas Elcock, Samuel Edge, Baltus Hagemon, John Williams and Richard Thompson.

Formal School Opening

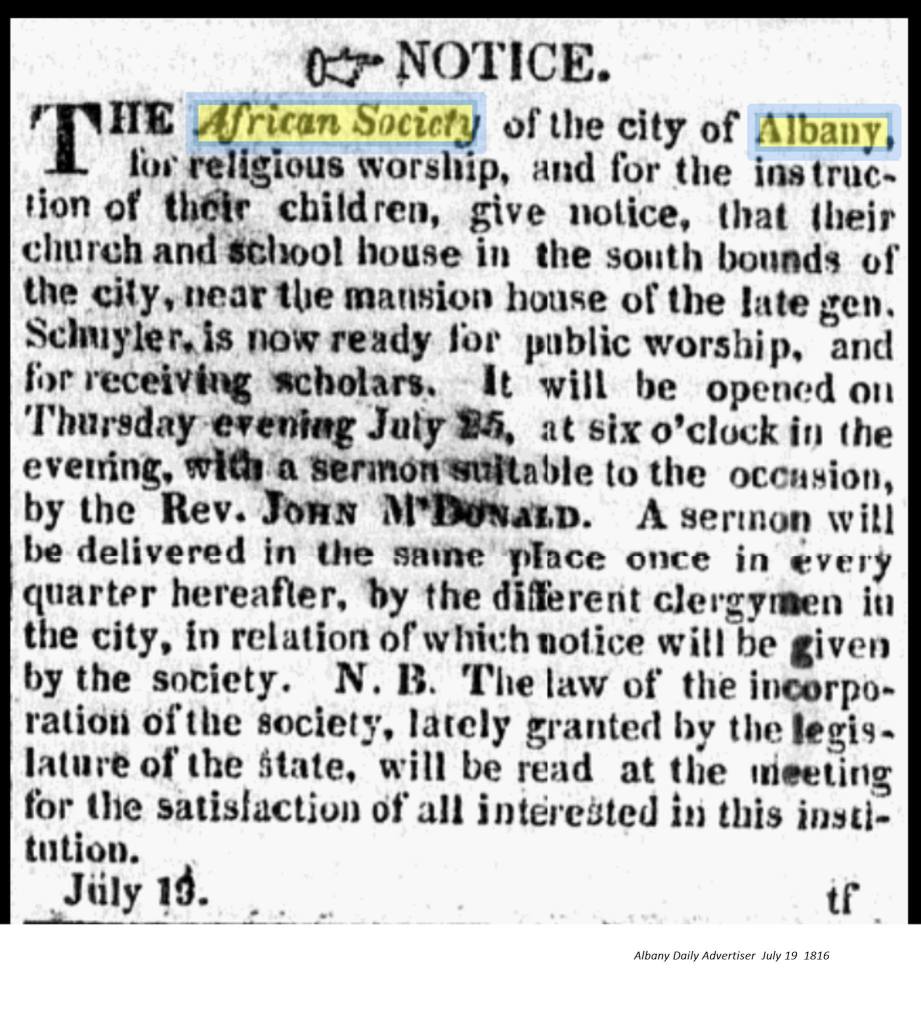

On July 19, 1816 the Albany Daily Advertiser published an announcement by the Albany African Society (for religious worship and for the instruction of their children). It stated that its church and school house (“… in the south bounds of the city near the mansion of the late Gen. Schuyler…”) was ready for public worship and receiving scholars.

“It will be opened on Thursday evening July 25 at six o’clock in the evening with a sermon suitable for the occasion by Rev. John McDonald.” (McDonald was the pastor of the United Presbyterian Church in Albany: In 1816 he was one of the four chaplains of the New York State Legislature.) It went on to say that a sermon would be delivered every quarter by a different clergyman in the city. Further it stated that the” law of incorporation of the society, lately granted by the legislature of the state” would be read.

And so, against all odds the African residents of Albany established a school formally recognized by New York State government.

The Continuation of the African Society

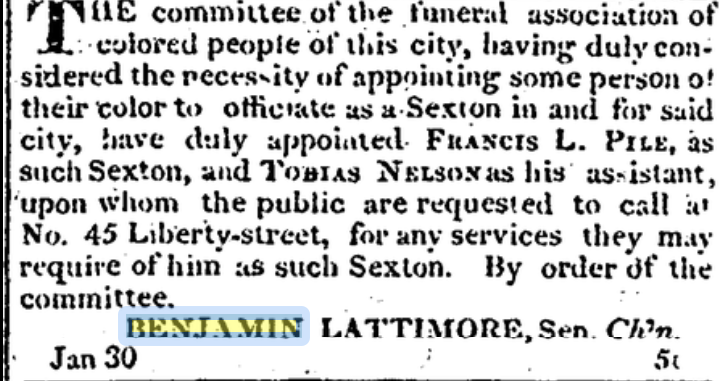

Scant evidence of the Albany African Society exists beyond the establishment of the school and the church in this time period. But what can be found makes it clear the Society continued working towards support of the Black community. In 1818 Ben Lattimore placed an announcement in the Albany Gazette in his capacity as Chairman of the Committee of the Albany funeral association of colored people. It referenced the “necessity of appointing some person of color as sexton”.. (At that time the sexton would have been the individual who was responsible for digging and maintaining graves.) He directed all persons to call upon Francis Pile, 45 Liberty St. (identified in city directory as a “waterman”) as the sexton or Tobias Nelson, assistant sexton, (a laborer who lived on Fox St. (Possibly “Bos Nelson” freed by John Pruyn in 1812. )

The need for “colored” sextons stemmed from an earlier decision by the Albany Council about burial of Blacks in the city. Around 1800 the Council established a large section of land on what was then the west edge of the populated portion of Albany as the city burial ground (known today as the State Street Burial Ground – Washington Park replaced the Burial Ground), The land was allocated among the various religious denominations in the city, and one parcel set aside for Africans. But over time the section that had been allocated for Africans turned out to be a prime location in the Burial Ground. In 1811 the Council rescinded the designation of the African lot, and allocated another less desirable section for their lot. This new designation required exhumations and reinternments in the new African section. The Council also decided that this task could only be performed by Black men

The Next Chapter

Slowly, life would improve for the Black community in Albany. In 1817 the New York State legislature would enact a law that would require the abolition of slavery in New York State for all enslaved people born in New York State on July 4, 1827. The end was near. And yet in the 1820 census there remained 108 enslaved people in the city of Albany.

The African School appears to have been successful. A small article appeared in the December, 1818 Albany Gazette. The writer had attended a quarterly exhibition of pupil performance at the South Pearl St. school .school. He indicated there had been a marked improvement since the previous exhibition. He wrote: “I congratulate my fellow citizens that they have such a school, and such a teacher in this place where children of colour are rescued from the abodes of infamy, ignorance and vice, and are instructed in the necessary branches of education and the Christian religion.”

Other schools for African children and adults in the city had been stablished. One was Sunday school opened by Mr. and Mrs. George Upfold and Mrs. Bocking at 3 Von Tromp St. (subsequently moved to the Uranian Hall at 67 North Pearl). Another Sunday school was established at the Presbyterian Church.

In 1819 W. Tweed Dale principal of Albany’s Lancaster School – a quasi- public school funded in part by the Common Council, established as school for African children. Dale was a Scotch immigrant and a very early radical abolitionist, and a true friend of the African population. (On his death in 1854 he left thousands of dollars to charities in Haiti, Africa and African Americans in the Mississippi Valley, to assist anti-slavery activities and to assist “fugitives” fleeing to the North.)

The Future

And so the African community in Albany had demonstrated that it could come together to create a better life and future, and begin to earn the respect of at least some of the city’s white population. Other Black men and women would come forward join with them, and continue to push for racial and social justice in Albany, and for the abolition of slavery the United States. By the 1830s Albany would become a cauldron of Black political and abolitionist activity and the a key hub of the Underground Railroad. White men and women in the community would join them.

Copyright 2022 Julie O’Connor